CMEPS-J Report No. 56 (April 16, 2021)

Shingo HAMANAKA

AbstractEight years have passed since the Syrian Arab Spring began. Many Syrian people lost their homes, assets, friends and family, and faced unparalleled tragedies. Today, the major war is over within the Syrian territory, aside from in the Idlib governorate. For Syrians, their work now focuses on the rehabilitation of their society and in rebuilding the Syrian Arab Republic. In other words, the people must again accept a social contract with a brutal and repressive authoritarian regime in the aftermath of the Syrian Civil War. Our research interest is as follows: How much patience do Syrian IDPs have in living with the political order as rebuilt by the Assad Administration and its allied nations? Despite calling it a “civil war,” the Syrian conflict has been internationalized by two camps (Russia and the United States). Therefore, in this study, we attempt to find evidence that recognizes the difference of attitudes toward the allies of Assad and the enemies of the IDPs and Syrian citizens in order to inquire about the psychological difficulties for people with severe experiences to accept Damascus’s authoritarian rule again. Keywords: Civil war, Syria, IDPs, international relations |

1. Introduction

The heart of the Syrian turmoil has already moved on to the process of nation rebuilding, rather than on the civil war itself. In using technical terminology from the classical state theory, the people are expected to codify a new social contract with the cold-blooded, repressive, and brutal government in order to stop the violence. In other words, “rebuilding Leviathan”[1] is the central issue in Syria. For more than eight years, the civil war has caused refugees to flee across the border alongside many internally displaced persons (IDPs). Their return and resettlement will be the key issue to “rebuilding Leviathan.”

This study deals with the political attitudes of the IDPs in Syria who are on the way to nation rebuilding, especially with the nation reunification by the people from Aleppo. A fierce battle was fought in the city of Aleppo during the Syrian Civil War, and the fate of the Allepian citizens was divided into becoming refugees in neighboring countries or becoming IDPs, we defined IDPs as, who lost their homes but could otherwise remain as residents within the Syrian borders, despite the hard-fought battles. When the people of Aleppo who have survived the serious armed conflicts return to being under the control of the Assad regime again, what do they think, and what are their political preferences in codifying a new social contract again?

We cannot measure the accurate support rate for the Syrian government because its cold-blooded and cruel authoritarian character is seen as being threatening from the viewpoint of the people. In other words, we cannot measure the validity of the social contract between the Assad regime and the Syrian people. Therefore, in this study, we take an alternative approach to measure the validity of the social contract by the indirect method of the political assessment of the United States as the strongest enemy against the Assad regime, and of Russia as the strongest ally with the Syrian government. The current situation in Syria is a rare and interesting case in the study of state-building at the time of its rehabilitation of its sovereignty, which gives us the chance to analyze this rare phenomenon as the codifying of the social contract again.

In the remainder of the article, we set up two theories—a pro-social attitude theory and a war-making apathy theory—based on the studies of political psychology in Section 2 and derive two hypotheses from these theories. In Section 3, we give an outline of the battle of Aleppo in order to show the context of this study. We explain the research strategy and dataset for empirical analysis in Section 4 and show the results of the statistical analysis in Section 5. In the last section, we discuss the result of the hypothetical test regarding the two theories and conclude by examining the implications of “rebuilding Leviathan” in Syria.

2. Theory

When a new political order is created within society, that is, when the people have escaped from a Hobbesian state of nature and decide to obey the sovereignty known as the Leviathan, any armed conflicts have already disappeared. Numerous studies have attempted to explain that authoritarian regimes, such as in Syria, have created order by using the distribution of resources along the multiple lines of social cleavage, and by the fear of secret police forces (Aoyama 2019; Heydemann and Leenders 2013; Hinnebusch 1990; Pearlman 2017). The literature on rebel governance, which has been rapidly developed in the field of civil war studies, has highlighted that separatist rebels seek to acquire legitimacy by the provision of administrative services to their inhabitants (Arjona Kasfir and Mampilly 2015). Some recent studies (Martinez and Eng 2017, 2018) have shown that a similar phenomenon was confirmed during the Syrian Civil War, where rebel forces made efforts to control steady supplies, the health care service, and the food supply to the inhabitants under their controlled areas.

However, from the perspective of service distribution probability, the Syrian government was superior to any rebel group because of its powerful resource distribution probability. Under the scarcity of goods during the war, it is thought that the Assad regime was powerful in comparison with the anti-governmental organizations from the viewpoint of the administrative services by securing the distribution route that included food, medical care, and public education. As of January 2020, the war is expected to be over without the Idlib province, and the government has given top priority to restoration following the postwar period. The success of the restoration means that the Assad regime will have succeeded in recovering public confidence and in increasing legitimacy in its governance. The restoration of Syrian society will depend on the explicit or implicit support of the deeply wounded people toward the Assad regime, which is namely that in which rebuilding the Leviathan would gain.

The Assad regime repeated indiscriminate bombing, particularly in air strikes with barrel bombs in the rebel-controlled areas of anti-government militias or ISIS. The Syrian government forces launched intensive and indiscriminate aerial bombing on Aleppo, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, Homs, Rif, and Damascus provinces. Fabbe, Hazlett, and Sinmazdemir (2017) investigated the impact of these indiscriminate air strikes on the political attitudes among Syrian refugees in Turkey to analyze the original survey data on them. According to Fabbe et al. (2017), the Syrian refugees who fled into Turkey had no representation of their own political positions in the Syrian political forces, despite indicating the menace of the Assad dictatorship. There are possible two interpretations for this result. One is that there were no representatives for the large number of Syrian refugees at the time of conducting the survey. In other words, the main forces of the Free Syrian Army, which continued fighting against the government forces in Idlib city, were volunteer Islamists forces. For the refugees, they were almost the same as the ISIS fighters who started to escape from the battlefields during that period. The other interpretation is the possibility that the refugees fell into political apathy by responding with the brutal attacks of the government forces.

It is interesting to note here the proposition that in the perspective of political psychology theory, a severe indiscriminate attack causes political apathy. Cautres (2011:84) shows that mass society theories explain the political apathy that appeared in urban inhabitants as being because they were separated from their primary groups in the wake of World War II. A civil war can have a separation effect on an individual who was forcibly removed from their family or hometown, and this may cause political apathy or a lack of interest in the sense of politics among the IDPs. It is not clear whether these attitudes truly arise from apathy, or whether they are pretending to be indifferent in consideration of their surrounding environments. This challenge could be overcome by repeating similar questions to measure the consistency of attitudes, and by conducting experimental surveys. We will refer to this proposition as the apathy creation theory of war.

However, there is an argument that states that the members of a society who have experienced intense fighting will contribute to the post-war reconstruction and democratization by acquiring a pro-social attitude after the war. For example, in Nepal, after a violent civil war arose, it was reported that the community that lingers maintained a pro-social attitude, and that their pro-social attitude toward those who left the community was weak (Gilligan et.al., 2016). In other studies, Blattman (2009) also revealed that in Uganda, a person who was kidnapped to become a child soldier and rebel was found to be actively participating in politics in the democratized society after the civil war.

The pro-social attitude formation theory of war can be considered as an adaptation to the norms prepared by the surrounding environment in political psychology. For the above case in Uganda, the person’s career as a former rebel soldier would be susceptible to having negative recognition after the war. Therefore, young former rebel soldiers are more likely to behave in an excessively adaptive manner toward postwar social norms. The same mechanism is considered to work in the example of Nepal.

In the case of Syria, who did not democratize after the civil war, but the authoritarian regime won, it would be considered as having a pro-social attitude to follow the standards prepared by the Assad regime. Adaptation toward the governmental code of conduct can be observed by survey scans. Moreover, it is not necessarily the case that behavior is an act that expresses the true intentions of the resident. Even if the norm is deceptive and ridiculous, it is essential that following it be considered as pro-social by others[2].

3. The Battle of Aleppo: The Most Important Regional Battle of the Syrian Civil War

Aleppo was one of the largest battlegrounds in the Syrian Civil War. Aleppo is the second largest city of Syria and had flourished as the commercial capital for a long time. During the outbreak of war, the territory under the control of the Assad regime only consisted of the area containing the University of Aleppo, the western Aleppo district where the Syrian military base is located, and Aleppo International Airport in the suburbs. The mostly eastern districts of Aleppo city were “liberated” by the Syrian Free Army, and much of the city block was ruled by the rebels. In addition, ISIS occupied Raqqa, the city in Aleppo’s neighboring prefectures, as its “capital.” ISIS declared “the founding of a nation” and extended its control to Aleppo province. As a result, Aleppo became the stage in which the three forces of the Assad regime, the Free Syrian Army, and ISIS engaged in armed conflict.

The Battle of Aleppo is considered the most important battle in the Syrian Civil War (Uskowi 2019: 82). Aleppo is next to Idlib province, a rebel stronghold, and is also sandwiched between the ISIS-controlled Raqqa province. Aleppo was positioned as a base of the East-West trade route during ancient times, and it had been a large and prosperous city. Therefore, the thinking that “the one who controls Aleppo, controls the civil war” was created. This also meant that the Battle of Aleppo would be a disastrous battle.

The event which can be said to be a turning point in the war occurred in September 2015. At the order of President Vladimir Putin, Russian air forces launched a large-scale airstrike on ISIS. ISIS carry out a brutal rule reminiscent of the Middle Ages, and one that is based on the thought of reactionism, which attracts Islamists from all over the world who volunteer for combat. Major countries around the world began to consider intervening in the civil war in order to recognize ISIS as a terrorist organization and eradicate it (Phillips 2016: 213-231). At the same time, the Russian campaign was the first full-scale military intervention by a great power of international politics. The Russian military intervention supported the Syrian regime’s forces and targeted the attack not only on ISIS, but also on the other rebel militias such as the Syrian Free Army.

During the Battle of Aleppo, the Assad regime’s forces tried to win back control. The Syrian Armed Forces, which held air control, expanded the scope of their barrel bombs and repeated daily indiscriminate bombings on the eastern districts of Aleppo city. The attacks destroyed most of the city, and many residents lost their homes and became IDPs. In 2016, the power relationship in the city, which had been divided between the government forces and the rebels, was refurbished, and the Assad regime’s area of control expanded. In the same year, there was a siege by the regime’s forces and in December, the Battle for Aleppo came to an end with the withdrawal of the rebel forces.

4. Methods: Strategy and Data Collection

4.1 Research Strategy

The survey data available in this paper does not include any questions that directly ask about the faithfulness or sympathies toward the Assad regime[3]. The request containing the question items to measure the support for the government in regime-controlled areas was rejected by the Syrian Opinion Center for Polls and Studies (SOCPS), the research agency in Syria. Therefore, we had to use another method to measure attitudes. Although in recent years, a popular method is to use a list experiment, it is not used in our three surveys: the Syrian IDPs Survey (2018), the Middle East poll (Syria, 2017), and the Syrian refugees in Turkey survey (2017)[4]. The research team took advantage of the fact that the Syrian Civil War has become internationalized, that is, it has been intervened by the major international great powers such as the United States and Russia, and by neighboring countries such as Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. In other words, Russia and Iran, who have clearly sided with the Syrian government, are treated as “agents of the Assad regime,” while the United States, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia are treated as “rebel agents.”

The three surveys included questions that evaluated the foreign countries’ involvements in Syria. When people who accept the authority of the government evaluated the foreign countries, the response of “highly appreciate the Russian performance, and have a reduced evaluation of the American performance” showed that the regime was treated as a norm. In other words, the people predicted that they would show obedience to the authoritarian regime, or a pro-social attitude, by favoring the allies and take action to refuse the enemy. This prediction is consistent with the pro-social attitude formation theory of war.

The most authoritarian regime may not require active obedience to its rulers. Unlike the totalitarian system, if an authoritarian regime is not obedient, yet has been depoliticized, it cannot become the object of surveillance. As Linz’ (2000: 167) classic argument shows, if an authoritarian regime lacks the effectiveness of political mobilization, then this ultimately leads to the apathy of the regime’s supporters. Regardless of the type of political system, if political indifference is prevalent among the people, the political system will become stabilized without accountability for its governance (Almond and Verba 1963; Huntington 1968). This prediction fits the apathy creation theory of war.

The context of this study is to view the Assad regime, which survived the Syrian Civil War, as a Leviathan that will be regenerated, and to understand the characteristics of the political attitude toward the Leviathan. The intensity of the battles that people have been exposed to is the main independent variable. What political attitudes do people form after being exposed to intense fighting? That is the issue at hand in this study.

In this study, the participants can be classified into IDPs, citizens, and refugees; all of whom experienced the Battle of Aleppo. “Citizens” here refers to the people who were lucky enough to maintain their own homes during the Syrian Civil War and did not lose their homes. More specifically, the citizens are from and reside in Aleppo province, and are considered as the least injured people from the Battle of Aleppo. The IDPs refer to those who had to abandon their homes and flee to areas considered as safe. Refugees are referred to as those who fled from their homes as well, but the difference between themselves and the IDPs depends on whether they crossed the border or not. That is, the IDPs here refer to those who remained in Syria, from Aleppo province, who became IDPs inside the territory controlled by the Assad regime. Refugees are also limited to those from Aleppo province and are also referred to as the people who were evacuated across the northern border into Turkey.

In terms of the intensity of the battle, it is impossible to determine whether the IDPs or refugees had more experience on average in being involved in the fierce fighting. However, the IDPs that remained in the territory without crossing the border between Syria and Turkey were expected to be better adapted to social norms under the Assad regime than the refugees who evacuated to Turkey. Since the Turkish government was supporting the rebels in the Syrian Civil War, it is predicted that those who became refugees would act against the norms within Syria. The IDPs from Aleppo province would also find differences between the people staying in Aleppo and those who fled to other prefectures. On average, the IDPs that remained in Aleppo province until 2016 seem to have had more experience in facing intense fighting. Therefore, this study chose an IDP-focused analysis.

From the above discussion, the following hypotheses are proposed. We derived both hypotheses from the pro-social attitude formation theory of war and the apathy creation theory of war:

H1: The higher the battle intensity, the more likely people are to be obedient to the authoritarian regime.

H2: The higher the battle intensity, the more likely people are to fall into apathy.

4.2 Survey Projects

The population of the survey projects were IDPs from Aleppo, Syrian citizens in Aleppo, and Syrians from Aleppo living in Turkey as refugees. The three parties of IDPs, citizens, and refugees were collected in separate polls.

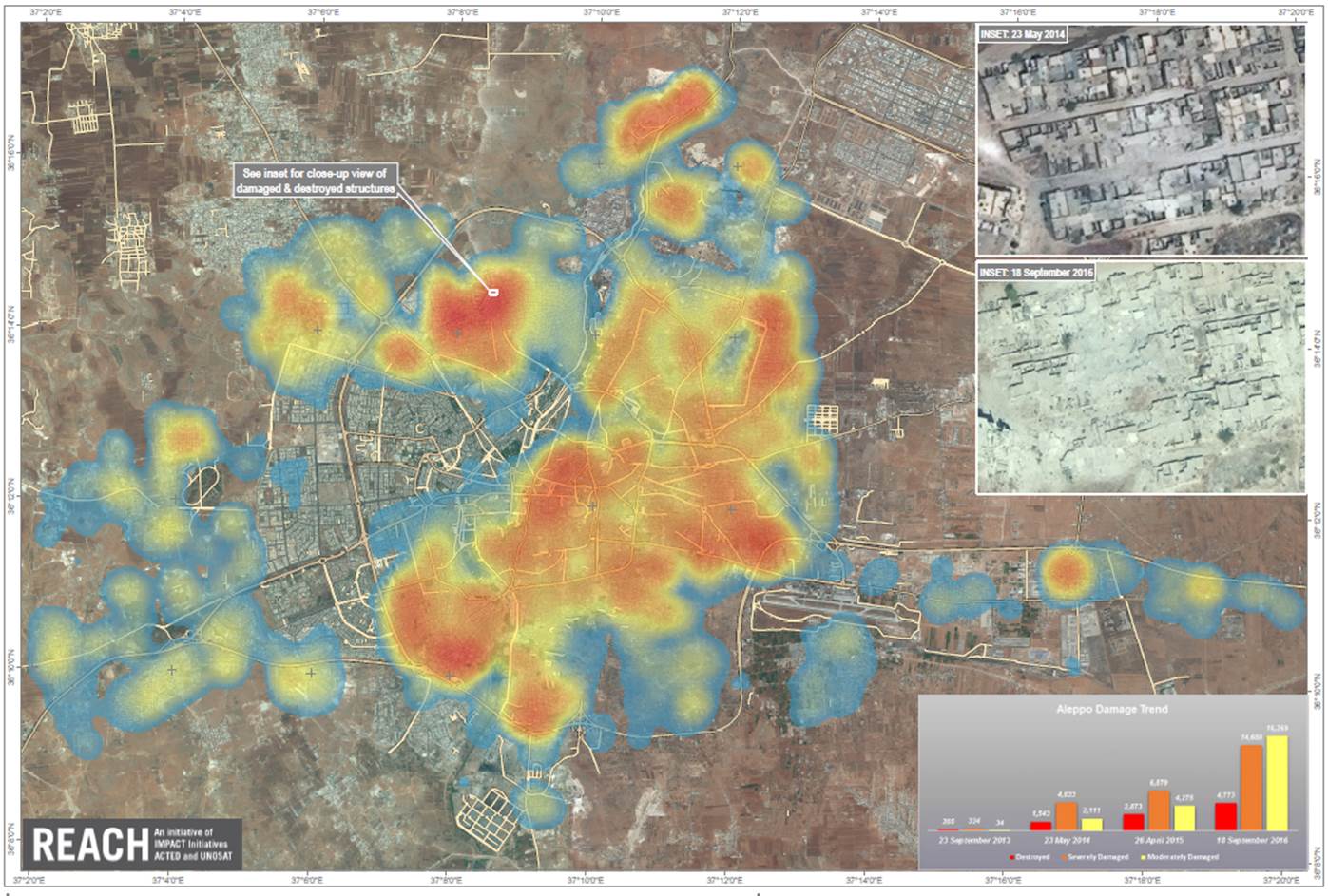

The Syrian IDP survey was conducted in September 2018 using face-to-face interview in Arabic The survey took place using 1,499 Syrians who were displaced since 2011 as a result of the Syrian Civil War, and who were between the ages of 18 and 70. The review was conducted by SOCPS, but the chart was designed by a research team which included this study’s author. SOCPS also conducted inspections in five prefectures other than Aleppo province (Damascus, Rif-Damascus, Homs, Latakia, and Hasaka). In this survey, the sample of the people from Aleppo prefecture was extracted based on the 2015 census data owned by the Central Bureau of Statistics of the Cabinet Office and was carried out by using the quota method. The target of the Aleppo province investigation was limited to the districts in Aleppo city and contained the areas featuring the western districts formerly controlled by rebels which the Assad regime forces then recaptured by airstrikes, shelling, ground battles, and so on (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Satellite-Detected Damage Map of Aleppo

Source: United Nations Institute for Training and Research. Imagery Analysis December 15, 2016.

The Middle East poll (Syria, 2017) was conducted in March 2017 by a face-to-face interview method in Arabic. The subjects of the study were Syrian nationals and men and women living in the Syrian Arab Republic between the ages of 18 and 65. The review was conducted by the same research agency (SOCPS) as the IDP survey, but the design of the questionnaire was done by a team of which the author was the research representative. The SOCPS inspection was also carried out in five prefectures other than the Aleppo province (Damascus, outside of Damascus, Homs, Latakia, and Hasaka). In this survey, the sample of the people from Aleppo prefecture and the residents were extracted based on the 2004 census held by the Central Bureau of Statistics of the Cabinet Office, the 2011 demographic estimation by the Bureau of Statistics, and the SOCPS survey team’s estimates, and these were used in the stratified two-stage random sampling method. The survey of Aleppo province was carried out mainly in the districts of Aleppo city, which was used in this study. The target area for investigation was the region controlled by the Assad regime which had been excluded from airstrikes.

The Syrian refugees in Turkey survey (2017) was conducted from the end of October to early November 2017, using a face-to-face interview method in Arabic. The population of the survey were Syrian male and female refugees living in seven Turkish provinces. The survey was conducted by the Infakto Research Workshop, but the questionnaire was designed by the research team which included this study’s author. Among the seven provinces in Turkey (Istanbul, Sanliurfa, Hatay, Gaziantep, Adana, Mersin, and Kilis), this study only utilized samples of people from Aleppo province. In the selected provinces listed above, neighborhoods were selected through consultation with the local authorities. The number of interviews conducted in each neighborhood was fixed at 12. In these neighborhoods, three streets were selected by using a Kish grid, and four interviews were completed in each street through random walks. The four provinces of Kilis, Gaziantep, Hatay (Iskenderun in Arabic), and Sanliurfa share a border with Syria, while Adana and Mersin are in their vicinity. Istanbul is far from the border but is the most populous city and close to Europe, so many Syrian refugees have emigrated from the southern provinces.

5. Results

Using the survey data conducted as discussed in Section 4.1, the attitude of obedience to the dictatorship, or the pro-social attitude, under the authoritarian Assad regime meant to highly appreciate the Russian performance as an “agent of the Assad regime,” and to reduce the evaluation of the United States as an “agent of the rebels.” However, a depoliticized attitude, or apathy, was considered as an inconsistent attitude regardless of whether it was pro-Assad or anti-Assad.

The IDPs living in Aleppo were considered as having experienced the battle, who have lost their homes, and who continue to be exposed to the aftermath of the battle. The other type of IDPs were born in but escaped from Aleppo and went to other cities in the wake of the battle. Therefore, the IDPs from Aleppo could be seen as having experienced fewer combats. The surveys on the Syrian citizens in Aleppo and the Syrian refugees had different questions than the survey on the IDPs in order to measure their political attitudes. Therefore, we used the measurements as a reference. Among the questions included in the Syrian IDPs, the following five questions were used in the analysis of this study:

(a7) To what extent do you believe that the following countries or organizations will contribute toward the improvement of living conditions?

(a8) To what extent do you believe that the following countries or organizations will contribute toward the rehabilitation of internally displaced persons?

(a9) To what extent do you believe that the following countries or organizations working within Syria during the crisis have supplied citizens with necessities?

(a10) To what extent do you want the following countries or institutions to invest in Syria?

(a13) To what extent do you want the following countries or organization to participate in the reconstruction of Syria?

The Syrian IDPs survey provided the above questions to 18 foreign countries and international organizations, and in this study, the questions from the improvement of living condition (a7) to participation in the reconstruction (a13) were used as measurement variables of political attitudes toward the United States and Russia. The answers from (a7) to (a13) contained five choices, and the respondents chose from: (1) Very much, (2) much, (3) moderately, (4) not so much, and (5) not at all.

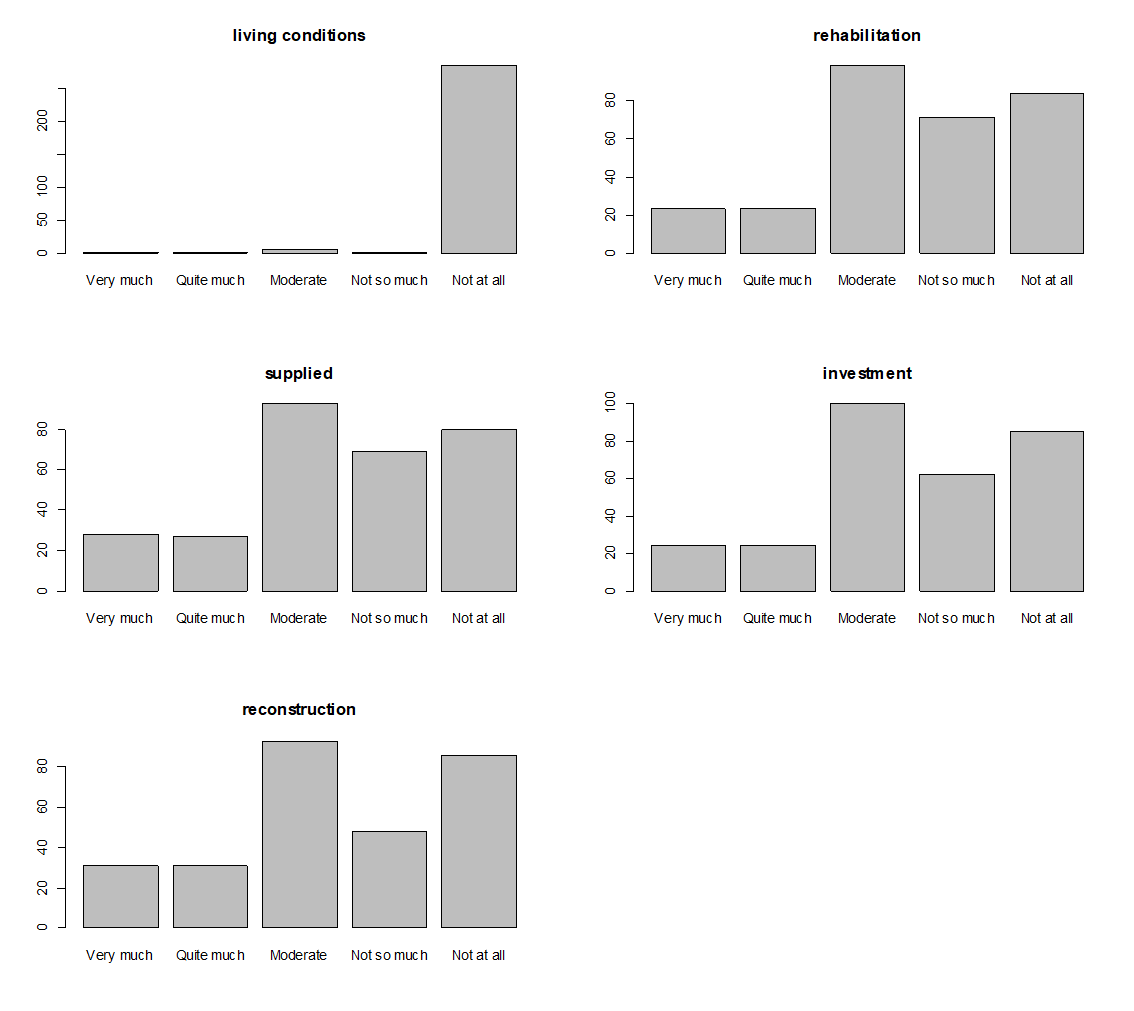

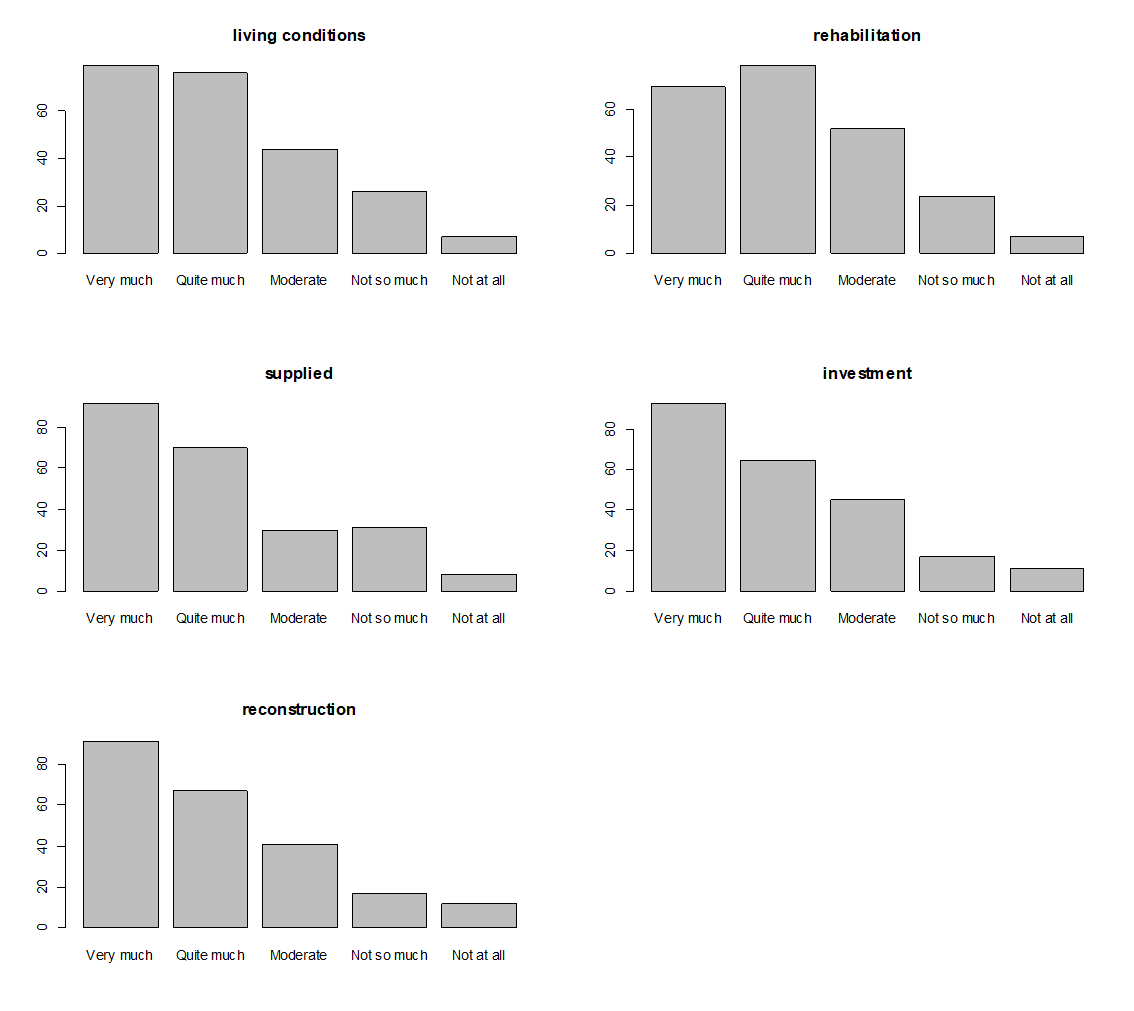

Fig. 2 represents the response distribution toward the United States, for (a7) to (a13), of the Aleppo resident IDPs. For question (a7), the pros and cons of having the living situation improved by the United States, the answer is concentrated on choice being “not at all.” However, when we reviewed the questions about the rehabilitation of the IDPs (a8), provision of necessary supplies (a9), investments for Syria (a10), and the reconstruction of Syria (a13), the answers are distributed from “moderate” to “not at all.” When compared to the IDPs response distribution toward the US, who were evacuated to other cities from Aleppo as shown in Figure 3, the characteristics of the distribution in Fig. 2 are clear. Fig. 3 has a distribution for all questions with roughly a tail on the left. In other words, the IDPs from Aleppo had a remarkable attitude toward rejecting the United States, and the proportion of vague attitudes, that is, the answer of “moderate,” from the IDPs from Aleppo were lower than those of the IDPs that remained in Aleppo.

Figure 2: Frequencies of attitudes of IDPs in Aleppo toward USA

Figure 3: Frequencies of attitudes of IDPs from Aleppo toward USA

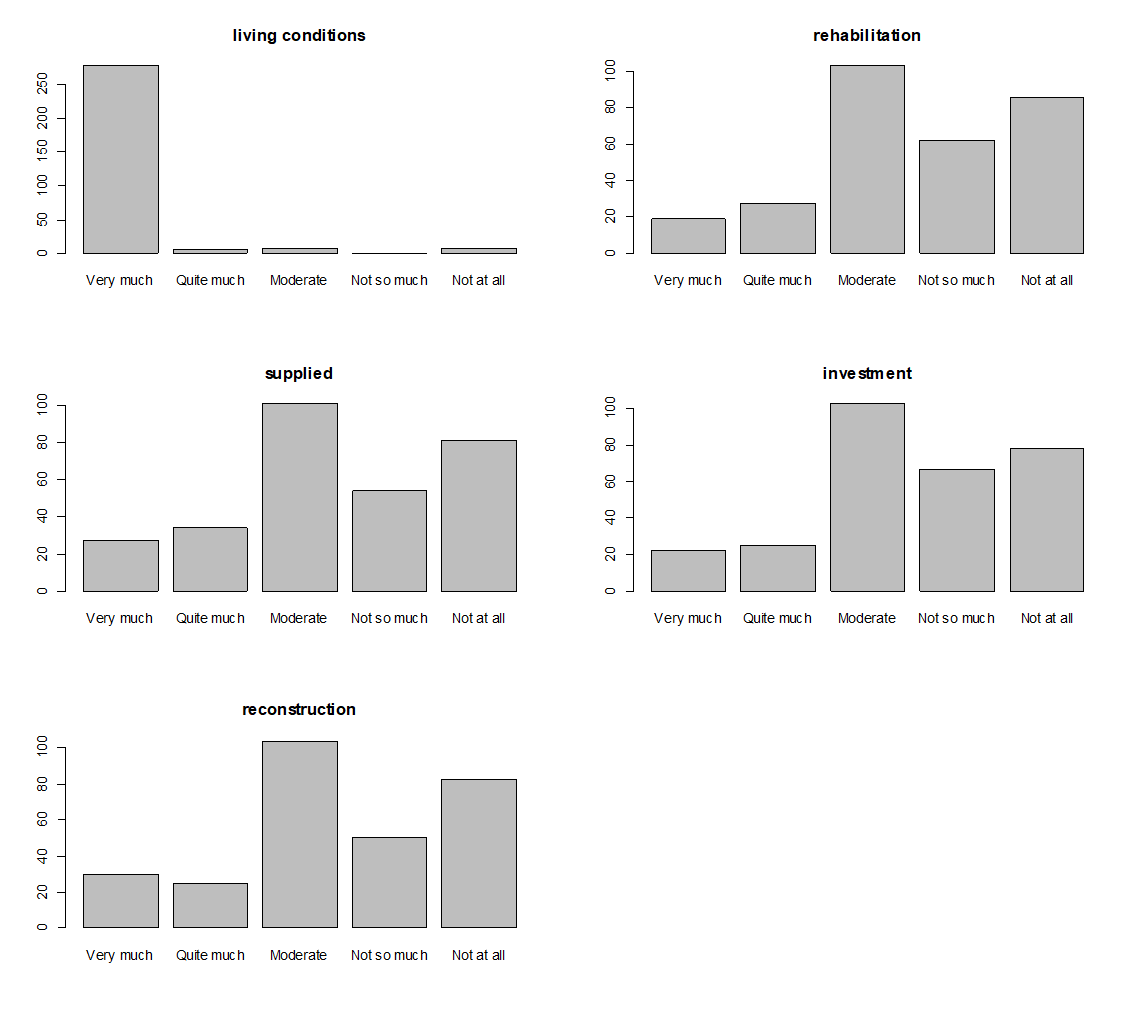

So, what attitudes do the IDPs have toward Russia, the agent of the Assad regime? Figure 4 represents the distribution of the Aleppo resident IDPs responses to all five questions. The answer to question (a7), “Russia’s improvement of living conditions” is concentrated on the responses of “very much,” while the answers to the other questions are still distributed from the responses of “moderate” to “not at all.” More to the point, the distribution of responses to rehabilitation (a8) to reconstruction (a13) in Fig. 4 is similar to the distribution of responses to rehabilitation to reconstruction in Fig. 2. This results in the following possibilities: the Aleppo resident IDPs do not distinguish their attitudes toward the United States as the “agent of the insurgents,” and toward Russia as the “agent of the Assad regime.”

Figure 4: Frequencies of attitudes of IDPs in Aleppo toward Russia

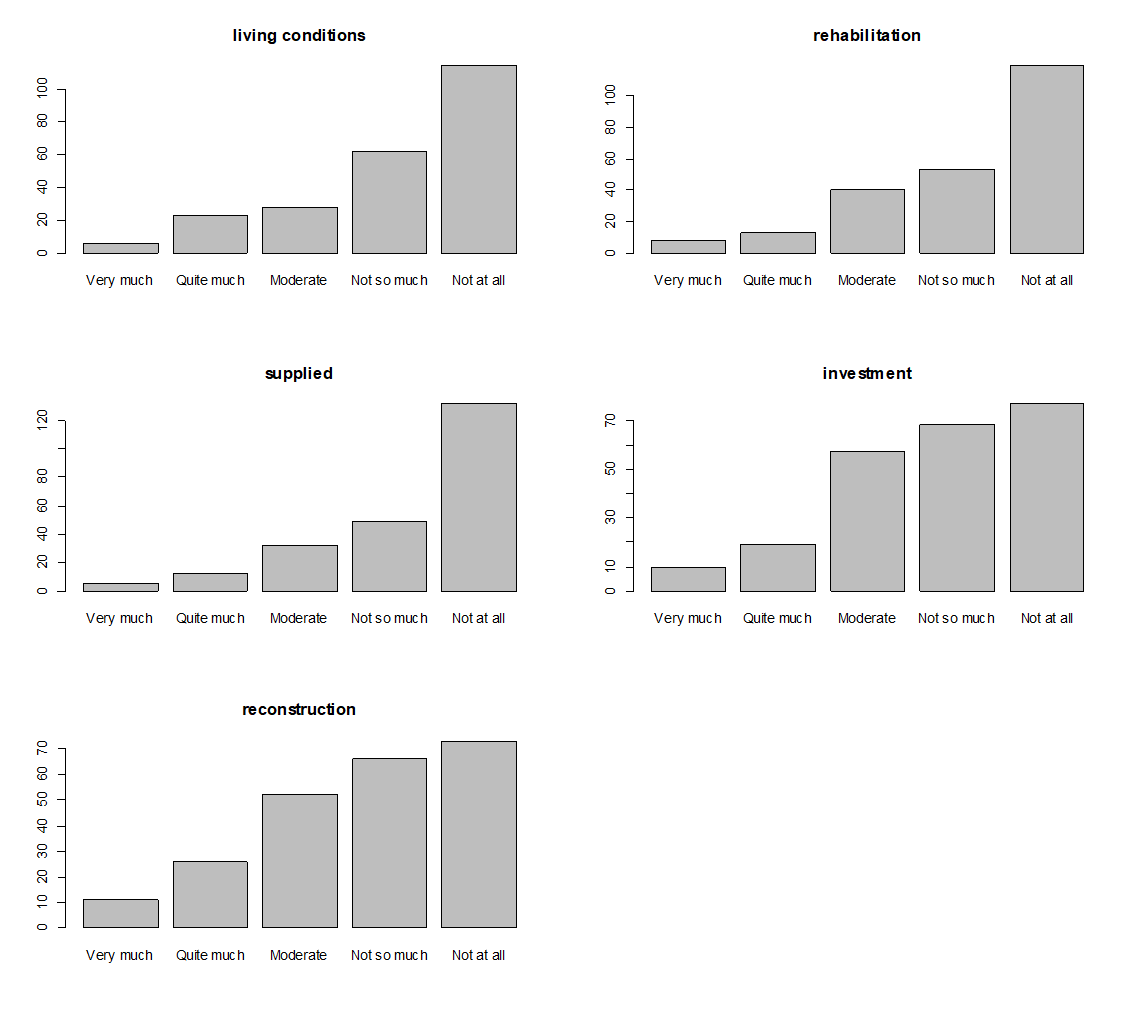

For the IDPs who fled to other cities in the wake of the Battle of Aleppo, their political attitudes toward Russia are summarized in Fig. 5. We can recognize the distribution with roughly a tail on the right for questions about reconstruction to living conditions. In other words, for Russia’s contribution toward improving living conditions (a7), rehabilitation of IDPs (a8), provision of necessary supplies (a9), investment in Syria (a10), and reconstruction of Syria (a13), the answers are concentrated into the responses of “very much” and “much.” The respondents have a positive attitude toward Russia as the “agent of the Assad regime.”

Figure 5: Frequencies of attitudes of IDPs from Aleppo toward Russia

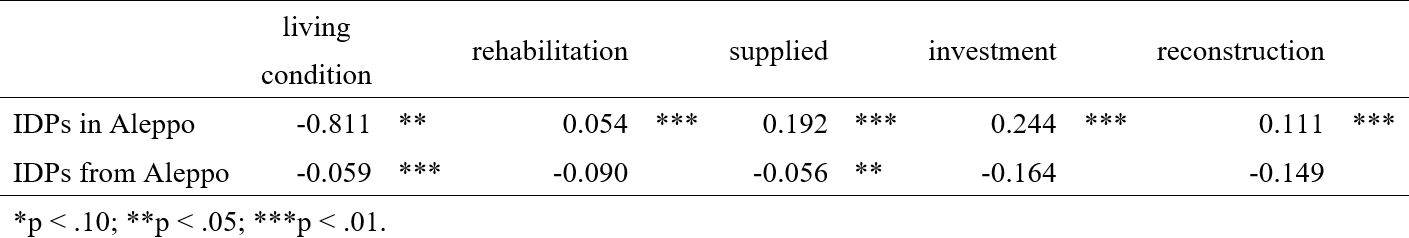

Table 1 shows the correlations between the evaluation of the United States and of Russia in each of the five questions, in which the IDPs living in Aleppo and the IDPs away from Aleppo responded to. The numerical values are polychoric correlation coefficients, and the calculation was performed using the maximum likelihood method algorithm. For the Aleppo resident IDPs, only the improvement of living conditions (a7) displayed a strong negative correlation between the evaluation of the United States and Russia. However, the rehabilitation of the IDPs (a8) later showed positive correlations. For the case of the IDPs living away from Aleppo, the correlation of the evaluation between the United States and Russia are negatively displayed in all questions.

Table 1: Correlation between USA and Russia

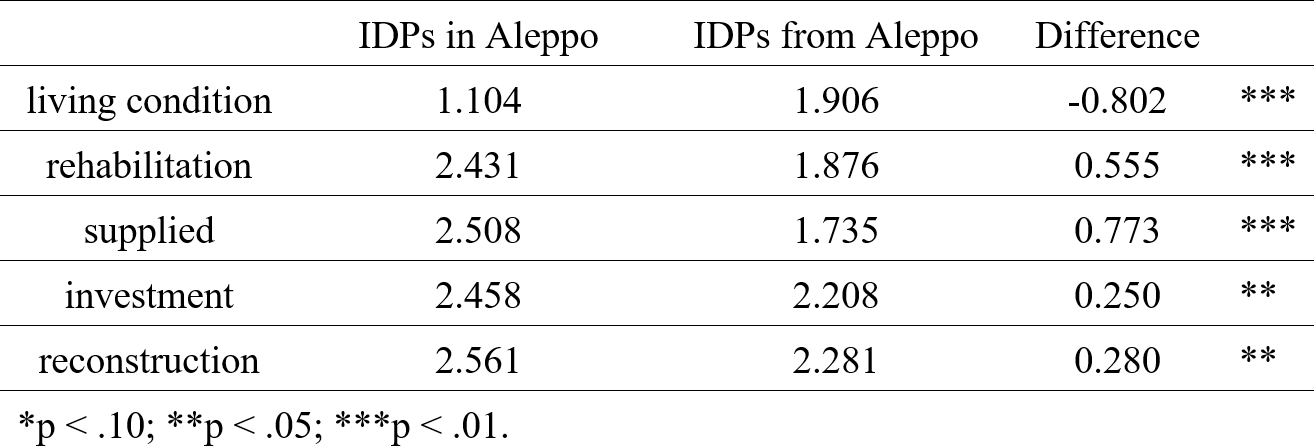

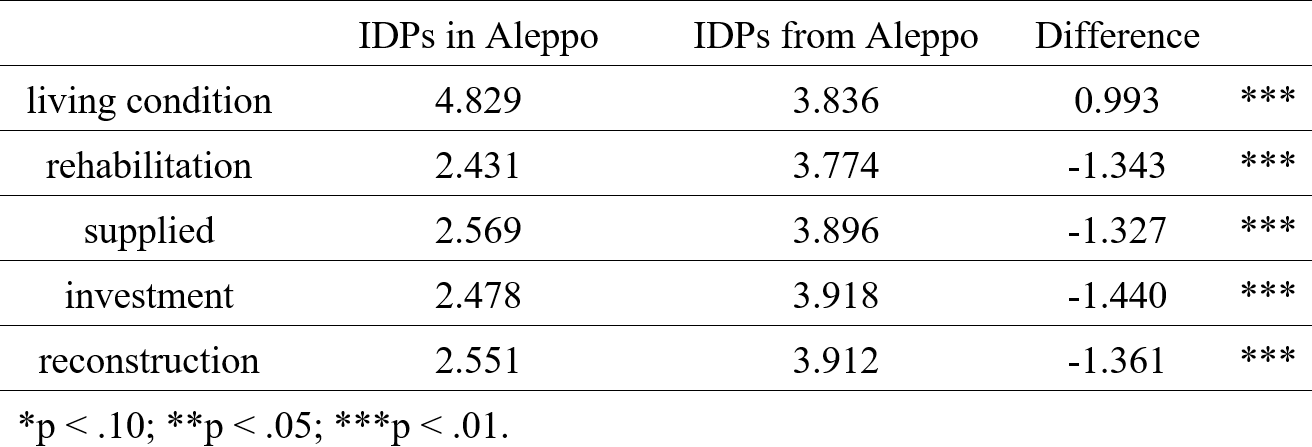

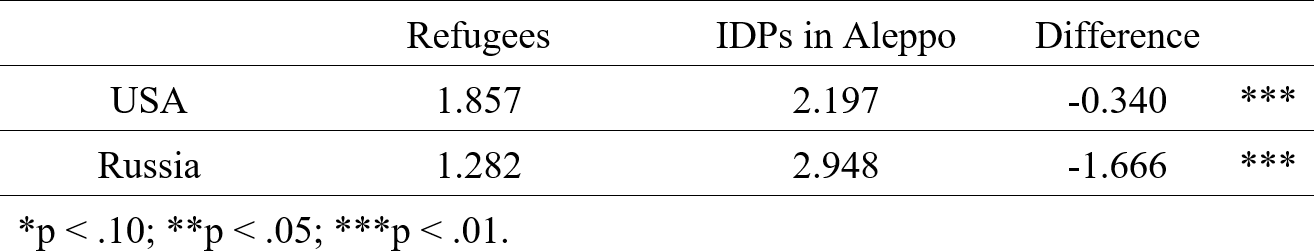

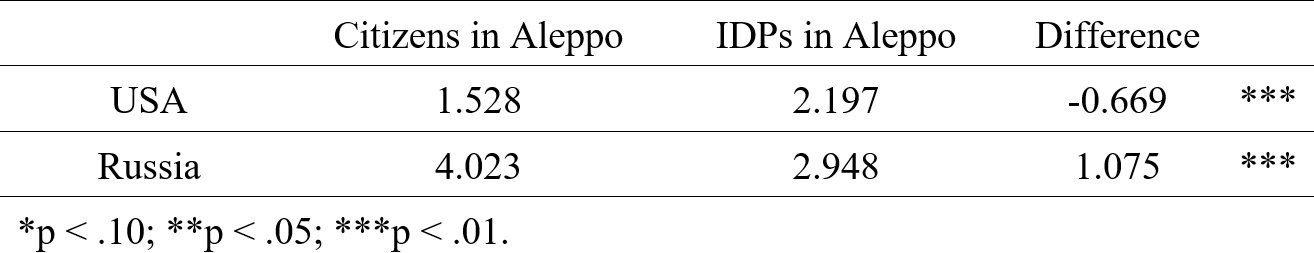

Table 2a indicates the results of the two-sample t-test for a difference in mean involving the sample of the IDPs from Aleppo and the sample of the IDPs in Aleppo about the evaluation of the United States, and Table 2b is the results of Russia. Since the numerical values were converted in reverse order, the larger the value, the better the evaluation. All questions except the improved living conditions (a7) reveal that the scores of the IDPs living away from Aleppo are lower for the United States and are more appreciative of Russia than those of the IDPs living in Aleppo.

Table 2a: Attitudes toward USA

Table 2b: Attitude toward Russia

Finally, let us compare refugees who fled from Aleppo to Turkey with the IDPs living in Aleppo, and compare the Syrian citizens in Aleppo with the IDPs living in Aleppo. The wording of the United States’ and Russia’s assessment of the Syrian refugee survey in Turkey was used, as follows:

“From the viewpoint of assistance to the Syrian people, how do you evaluate these countries?”

The wording of the evaluation of the United States and Russia used in the survey for the Syrian citizens is as follows:

“How do you evaluate the following countries, including Japan, from the perspective of giving aid to the Syrian people?”

In response to the above questions, respondents were asked to answer from the selection of: (1) very high, (2) high, (3) somewhat, (4) not very, and (5) not at all. In the operation of the variables and reverse order, it was changed so that the higher the numerical value, the higher the evaluation. For comparative study, the mean of the IDP’s answers in Aleppo to the previous five questions (a7 to a13) was taken and integrated into a single variable. Again, it was recoded in reverse order, and changed so that the higher the number, the higher the rating.

Table 3a shows the t-test result of the American and Russian evaluation by the refugees and the IDPs living in Aleppo. It can be seen that the refugees from Aleppo have a lower rating for both countries. Table 3b is the t-test result of the evaluation of the great powers by the citizens and the IDPs living in Aleppo. It shows that the citizens have a lower rating for the United States than the IDPs, and a higher rating for Russia.

Table 3a: Attitude toward Foreign Powers

Table 3b: Attitude toward Foreign Powers

6. Concluding Remarks

This study focused on ordinary Syrian people who had experienced indiscriminate bombing during the Battle of Aleppo and had then become IDPs, and the study clarified the characteristics of the political attitudes of the IDPs as shaped by the intense fighting. From the viewpoint of political psychology, we constructed two propositions: the apathy creation theory of war and the pro-social attitude formation theory of war. We derived two hypotheses from these theories, which were verified using basic statistical methods with the original datasets from the IDPs from Aleppo and the citizens and refugees survey projects. As a result of the statistical analysis, we can report the following three findings.

First, the IDPs in Aleppo, who lost their homes after experiencing the Battle of Aleppo but stayed in the city, revealed no significant difference in their attitude toward the United States and their attitude toward Russia when compared to the IDPs living away from Aleppo (Table 2a, 2b). In other words, the IDPs from Aleppo appreciate Russia as the agent of the Assad regime, and show a pro-social attitude to criticizing the United States as the agent of the rebels (Table 1, 2a, 2b). These results support the second hypothesis (H2) derived from the apathy creation theory of war, because the IDPs in Aleppo are considered to have experienced a higher intensity of battle than the IDPs that left Aleppo city.

Second, the IDPs in Aleppo expressed a pro-social attitude only in respect to the improvement in living conditions in question (a7) of Table 1, and (a7) of Table 2a and Table 2b. However, the associations between the evaluation for the United States and Russia had positive correlations in the items concerning the rehabilitation of the IDPs (a8), provision of necessary supplies(a9), financial investment (a10), and reconstruction of Syria (a13) in Table 1, with the exception of question (a7). These results are also consistent with the second hypothesis (H2) derived from the apathy creation theory of war and does not support the pro-social attitude formation theory hypothesis (H1) of war.

Finally, the refugees from Aleppo showed an attitude toward criticizing both Russia and the United States, while the Syrian citizens living in Aleppo evaluated the Russian performance and showed a pro-social attitude toward criticizing the performance of the United States. The political attitude of the IDPs in Aleppo had different characteristics from those of the refugees and the citizens. From the above discussion, the results of this study support the apathy creation theory of war and are inconsistent with the pro-social attitude formation theory.

As a result, we are faced with a people who have apathy due to their survival of the fierce fighting, and who are in the process of re-signing a social contract with the Assad regime. Although the Assad regime begins working on the post-war reconstruction of the state, the Syrian government is expected to implement reconstruction policies while being sensitive to the watchful eyes of Russia and Iran. If there are a large number of people falling into apathy, it will be considered convenient for the restoration of the authoritarian system. The more people there are that do not have a politically clear opinion, that is, the more depoliticized people there are, the more people there will be at the center of power who can survive politically in order to gain the support of the elite Damascus insiders. The rebuilding Leviathan, the state of Syria, will regain the face of a powerful dictator, even if it is step by step.

Notes

[1] Anna Grzymala-Busse put the same title on her book, but she treated with party competition process in developing the formal institution of the democratizing post-communist states (Grzymala-Busse 2007). However, this paper focuses not on party competition in democratization process but on the “Gligamesh Problem” (Acemoglu and Robinson 2019: xiii) which the people suffer tyranny of the Assad regime after finishing of the Syrian Civil War.

[2] Wedeen (1999) argued that Syria, under Hafez Assad’s regime, was governed by a kind of cult-like show. Wedeen insisted that people were disproportionately following the “visible cult-like show” that was found in symbols (e.g., posters and mass games) that saw Assad as a hero; which is the power base of the system.

[3] The researchers, including the author, went to Mersin province in Turkey to interview 10 Syrian refugees (February 17, 2019), but they were unable to hear political opinions about the Assad regime unless they were in their home space.

[4] We will give further explanation about the three surveys in the next section.

References

- Acemoglu D, Robinson JA. The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. New York: Penguin Books; 2019.

- Almond GA, Verba S. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. London: SAGE; 1989.

- Aoyama H. 2019. “Syria: Strong State Versus Social Cleavages.” In: Matar L, Kadri A, editors. Syria: From National Independence to Proxy War. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019. p.71-92.

- Arjona A, Kasfir N, Mampilly Z, editors. Rebel Governance in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

- Blattman C. “From Violence to Voting: War and Political Participation in Uganda.” Am Polit Sci Rev. 2009;103 (2): 231–47.

- Cautres B. Apathy In International Encyclopedia of Political Science. London: SAGE, 2011; p.84-86.

- Fabbe K, Hazlett C, Sinmazdemir, T. “Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes among Syrian Refugees in Turkey.” Harvard Business School BGIE Unit Working Paper, no. 18-024; 2017.

- Gilligan MJ, Pasquale BJ, Samii C. “Civil War and Social Cohesion: Lab-in-the-Field Evidence from Nepal.” Am J Polit Sci. 2014;58 (3): 604–19.

- Anna Grzymala-Busse A. Rebuilding Leviathan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

- Hinnebusch RA. Authoritarian Power and State Formation in Ba’thist Syria. Boulder: Westview Press; 1990.

- Huntington SS. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Heaven: Yale University Press; 1968.

- Heydemann S, Leenders R. Middle East Authoritarianisms. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2013.

- Linz JJ. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2000.

- Martínez, JC, Eng B. “Struggling to Perform the State.” Int Polit Soc. 2017;11: 130-147.

- Martínez, JC, Eng B. “Stifling Stateness.” Security Dialogue. 2018;49 (4): 235–253.

- Pearlman W. We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled. New York: Custom House; 2017.

- Phillips C. The Battle for Syria. New Heaven: Yale University Press; 2016.

- Tilly C. 1985. “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime.” In Evans P, Rueschemeyer D, Skocpol T. editors. Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985; p.69-191.

- Uskowi N. Temperature Rising. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2019.

- Wedeen L. Ambiguities of Domination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999.